Born and raised in Ljubljana, Slovenia, I came to Chicago five years ago to pursue a PhD in English at Northwestern University. While I remained confined to books and the far north side during the first two years of my graduate program, I grew to know and love the city and its many different neighborhoods over the past three. As I wrote in a previous post, I joined the Humanities Without Walls grant on Indigenous Art and Activism in Changing Climates: The Mississippi River Valley, Colonialism, and Environmental Change with a dissertation project on the Mississippi River in post-Twain literature underway, but had very little background in American Indian Studies. Learning from site visits and Indigenous artists, activists, and scholars working in the field, I began to feel more grounded and started having a greater sense of all the absences and omissions in my knowledge of American history and culture. I was still taken by surprise, however, when our team met in Chicago, the city I’ve come to consider home, in the spring of 2019, and I learned about the vibrant Native American community in the greater Chicago area—about 65,000 people from over a hundred tribal nations, according to the American Indian Center of Chicago—and the art and activism that come out of it. How could I have missed this? The keywords and map below reflect how the HWW project has shifted my understanding of Chicago and the Midwest, showing them as the Indigenous hubs that they are.

Remapping

How do you map a story? What would happen if representations of Native Americans in art and culture centered the landscapes that emerge out of Native memories, stories, and poetry instead of dwelling on colonial erasures and conventional maps that cover up Indigenous presence? These are some of the questions Citizen Band Potawatomi artist and cartographer Margaret Pearce addresses in her work, which has taken her to New Orleans via Chicago as she examines public opinion about flooding to create an Indigenized map of the Mississippi River. While in residence at Northwestern University in Evanston, IL, just north of Chicago, Pearce shared some of her work with our Humanities Without Walls group and led us through a workshop that redefined mapping.

The workshop with Pearce made me see the poem “New Orleans” (1983) by U.S. Poet Laureate Joy Harjo (Creek) in a new light. “New Orleans” traces Indigenous histories of the city through cartographic language, i.e. the language of mapping used in poetic form, linguistically and creatively remapping sites of erasure as places of Indigenous presence and rhetorically bringing Native people into the present. I borrow the term ‘(re)mapping’ from Gender and American Indian Studies scholar Mishuana Goeman (Tonawanda Band of Seneca). Goeman describes Indigenous (re)mapping as a creative process that first exposes colonial erasures and reveals the ways in which histories and landscapes get overwritten in settler historical memory, and then reclaims those spaces by presenting them in relation to contemporary Native experiences as well as to memories and stories that involve specific geographies and ancestors. In other words, remappings reject the concept of ownership and describe geography in terms of relationships—to the land and to one another, to the past and to the future.

Harjo’s poem serves as one example of such a remapping, linking post-removal Oklahoma to ancestral Creek lands along the Lower Mississippi through representations of memory and the metaphor of the river’s geography: “I have a memory. / It swims deep in blood, / a delta in the skin. It swims out of Oklahoma, / deep the Mississippi River.” These lines present memory as embodied—not only does it act with agency; it is also embedded in blood, the fluid that keeps us alive. At the same time, the image of a “delta in the skin” maps geography onto the body, highlighting Indigenous people’s relations with the land. The speaker compares ancestral memories encoded in the body to the Mississippi River delta south of New Orleans, a striking landform created by sediment deposition that is etched into the land in a vein-like pattern. The image of the body as land shows the two as inextricably linked, but it also connects Creeks’ ancestral lands along the Lower Mississippi River with their post-relocation territory in Oklahoma, expanding the notion of homelands. The speaker’s memory and the poem itself carry forward the voices that the lines describe as buried in the Mississippi mud. By giving visibility to Indigenous presence in New Orleans and claiming lost territory through the act of writing, the speaker is resisting the erasure and dispossession attempted by relocation and asserting the Creeks’ claim to the Southeast (listen to Harjo’s reading of the poem here).

Indigenous Chicago

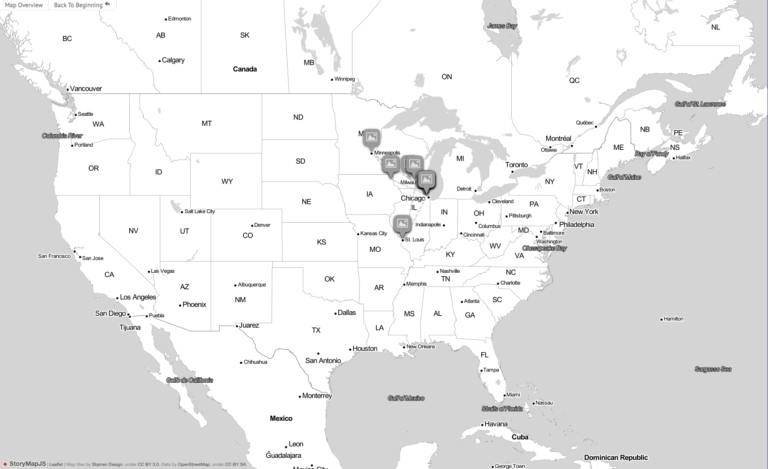

Margaret Pearce’s mapping workshop and the artists we met also made me see Chicago, the city I have called home for the past five years, as the Indigenous hub that it is. The interactive map I made in response to the experience is best viewed following the link above. The area of what is now known as Chicago is the traditional homeland of the people of the Council of Three Fires: the Potawatomi, Ojibwa, Odawa, as well as the Miami, Ho-Chunk, Sac, Fox, Menominee, and Mesquakie. The 1833 Treaty of Chicago, a consequence of Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act of 1830, pushed Native tribes west of the Mississippi River to clear the space for European settlement, resulting in mass exile and dispossession. This set the stage for the 1837 incorporation of Chicago, the world’s fastest growing city in the nineteenth century. But some Native people refused to be removed, remaining in Chicago and the region. In the 1950s, the assimilationist federal policies of American Indian Urban Relocation moved many Native people from reservations across the country to big cities like Chicago, Seattle, Los Angeles, Denver, and Cleveland. In this way, Chicago became an important Indigenous center once again, and the city continues to be a place of activism, art, and belonging for Native people throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. According to the American Indian Center of Chicago, American Indians from over one hundred tribal nations live in Chicagoland today, making it one of the larger Native American urban centers in the country. The official population count for Cook County, Illinois currently stands at over 38,000. For more on this history, see Rosalyn LaPier and David Beck’s City Indian: Native American Activism in Chicago, 1893-1934 (2015), John Low’s Imprints: The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians and the City of Chicago (2016) and Laura Furlan’s Indigenous Cities: Urban Indian Fiction and the History of Relocation (2017).