I think Indigenous science should be studied more. We did not live in wilderness before colonization, but in areas in which the surrounding landscapes were heavily engineered, using advanced agricultural science.

Jeffery Darensbourg

Writer, public speaker, researcher, zinemaker, and provocateur Jeffery U. Darensbourg, Ph.D., is a Louisiana Creole of mixed ethnicity and an enrolled member of the Atakapa-Ishak Nation of Southwest Louisiana and Southeast Texas. He is the founder and Editor-Who’s-not-a-Chief of the zine Bulbancha Is Still a Place: Indigenous Culture from New Orleans. He has served as a writer in residence at Tulane University’s A Studio in the Woods and a Monroe Fellow of the New Orleans Center for the Gulf South at Tulane, working on a book-length study of the Atakapa-Ishak of Southwest Louisiana. Jeffery is currently serving as a 2020-2025 Fellow of the Center for Louisiana Studies at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

In 2020, Jeffery was scheduled to join our Humanities Without Walls project in Louisiana to talk about his work in and around Bulbancha, but the pandemic prevented the meeting from taking place. He is in conversation with Sara Černe here.

1. Tell us about Bulbancha, the place as well as the zine, and about how you came to this project. How does Bulbancha differ from New Orleans and how would you characterize its relationship to the Mississippi River?

It may seem like an odd assertion, but I will make it boldly anyway: “New Orleans” does not exist. I’ve made that assertion in print, in talks, and even on public radio. At least, I refuse to use that term to refer to a geographic area. The rallying cry “Bulbancha is still a place” is something I mean quite literally. I mean it for several reasons, involving both my own views about the Doctrine of Discovery as well as the nature of this city culturally. I first used the phrase in a conference talk at Tulane in 2018. The word “Bulbancha” is spreading in its reach. It was finally mentioned in the New York Times recently, though in a different spelling than the one I use, which is fine, as there are multiple orthographies of the Choctaw language. I learned the word in January 2014, when I moved to Bulbancha from Pinhook/Kiwilš Nuņ, depending on which Indigenous term one wishes to use for so-called Lafayette, Louisiana. I have subsequently written about the word in several places, including in recent chapters both in the Prospect.5 catalog and in an important new book on Louisiana Creole peoplehood. My friend Ozone504–that’s his nomme de guerre–and I began doing single-word activism in the runup to the 2018 Tricentennial of (the Colonial Occupation Known as) New Orleans. We also made two issues, so far, of a zine, Bulbancha Is Still a Place: Indigenous Culture from “New Orleans,” which as far as we know is the only published anthology of Indigenous writing and art from Louisiana. It shouldn’t be, though. I love it when someone uses the word who has never heard of either of us.

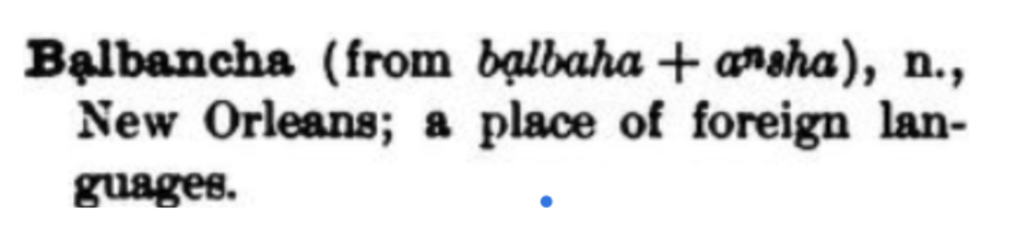

So, what even is Bulbancha? It is an Indigenous name for the place where I live, a place colonists tried unsuccessfully to rename as “New Orleans.” I say “unsuccessfully” because there are still people who use the original name, and who refuse to use the colonizer name. I am involved in Indigenous language reclamation of Ishakkoy, a language incorrectly known as Atakapan. From that I have become leary of exact translations, but “Bulbancha” refers to the presence of languages other than Choctaw spoken in the area. It means “a place of other languages.” I found it originally in the Choctaw dictionaries of both Chief Allen Wright, the one who named the State of Oklahoma, and missionary Cyrus Byington. There are other Indigenous names for the city, but the others either refer to its large size, as is the case with Nuņ Uš, meaning “Big Village” in Ishakkoy, or to the changing ethnic composition of the place, as in the Tunica name Tonrɔwahal’ukini, meaning “White Man Town.”

According to the standard naming practice of Indigenous Peoples in this hemisphere, a place takes its name from the most salient feature of the area. In this case, the salient feature in the name is the mixture of peoples at this confluence of waterways, Lake Okwatta (“Lake Pontchartrain”), Bayou Choupic (“Bayou St. John”), and the Mississippi, also known as the River Bulbancha. A road extended from the Bayou to the River, parts of which exist to this day (I talk about this road in a 2021 art project from Sarrah Danziger about missing parts of the city). Water traffic made Bulbancha a place of exchange between peoples before colonization. Some have suggested the name only arose after colonization, but that belief stems from a misunderstanding of naming practices. The presence of a couple of additional colonizer tongues would not compare with the existing diversity of languages, including Mobilian, Choctaw, Tunican, Chitimacha, Biloxi, Uma, Natchez, and on and on. (I discuss this matter in an endnote to my 2021 article in Southern Cultures, “Hunting Memories of the Grass Things: An Indigenous Reflection on Bison in Louisiana”.)

“Bulbancha” accurately captures the essence of this amazing city, and does it in a way that “New Orleans” never can.

It is a colonial construct that there is one huge river, which must have just one name everywhere. Here the River was called the Bulbancha. The word is used for the River in the first French book about the area, Le Page du Pratz’s Histoire de la Louisiane (1758); it is also used as a name for the River in the wording at the bottom of one of the earliest colonial images of Indigenous People in Louisiana, Alexandre de Batz’s “Desseins de Sauvages de Plusieurs Nations” (1735). While the French were correct that the River had such a designation here, the name also referred to the land itself. A mix of Indigenous Nations speaking different languages happened mostly on land. This is an obvious point, but many miss it. Even a sharp distinction between land and water here is a bit ridiculous at any point in Bulbancha’s history. It floods here, often, and with destructive effect. It has always flooded here. The history of this city involves constant efforts to control water and its flow. (For those interested in the topic, I highly recommend the relevant parts of Richard Campanella’s 2008 book Bienville’s Dilemma: A Historical Geography of New Orleans.)

2. You spent the first few months of the pandemic quarantining on the banks of the Mississippi during your artist residency at Tulane University’s A Studio in the Woods. What was the experience like and how has the river shaped your creative output and your relationship to Louisiana?

I am really grateful to A Studio in the Woods for giving me the opportunity to be out there for eleven weeks beginning in March 2020. I was often there alone due to the vicissitudes of the pandemic, and I walked up and down the banks of the River a couple of times per day (the River is across the road from this particular outpost of Tulane). I harvested driftwood from my strolls for making walking sticks in the woodshop there as a side pursuit, and I wrote. I thought of all of the people moving back and forth on the River. I thought of my own ancestors, of various sorts. Up and down that water they moved, Indigenous, West African, Spanish, French, German, and every mixture thereof. I had the time and space to really settle in and work on some essays, including the one on bison mentioned above. I also did a project I had wanted to do since linguist David Kaufman’s revised dictionary of Ishakkoy had come out, viz., making poetry and songs in Ishakkoy. I have written about this before. In short, it was tedious, and worth it. I began with the cento form, a type of found poetry, using example sentences from the Kaufman dictionary. I moved on to making my own sentences. Some of these poems have been published, and two were made into a film, as discussed below. My favorite of the centos is “Hoktiwe,” which appeared in Transmotion. A couple of these also made it into the Spring 2021 issue of Yellow Medicine Review. I foraged the surrounding woods, got pretty good at cooking bull thistle, and read and read and read. I grew up on the River, in Itta Homma (of which “Baton Rouge” is a translation), and live a five minute walk from the River in Bulbancha. Its proximity is a major feature of my personal geography.

3. In “Hoktiwe: Two Poems in Ishakkoy,” you worked with Fernando Lopez to create a short film featuring your poetry and music. Why is it important to you to work outside of a single medium and what are some of the highlights as well as challenges of collaborative work? What emerging or long-existing conversations/ confluences between Indigenous art and activism in the context of the Mississippi have been most meaningful to you?

Honestly, when I wrote the poems, I had no thoughts of making them into a film. Shortly after I finished my residency at A Studio in the Woods, I found myself in conversation with George Scheer, director of the Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans, about their annual open call exhibition. He asked if I might make some media of some of my writing, and offered to help fund a film. I was happy the Center included it in an exhibition, “Make America What America Must Become,” both at the CAC itself and online. Happily, an anthology of the Bulbancha Is Still a Place zine was also included in the online version of the exhibition.

The only person I even considered working with on the filming was Fernando López, an Indigenous master of the lens. This was my first time really combining my poetry and music, and it will not be the last. In the film I walk into the River itself. When we filmed, the water was low so I was able to wade in from the batture and write on the sandbar with a walking stick. Since childhood I have known of the danger of the current, but this time I was thinking about industrial pollutants. I wrote the word “hoktiwe” on the shore, as it was the theme of being in the River. That word means “we are together,” and the River represents that to me, containing the runoff of the work and cultures and garbage and dreams of millions across a vast swath of our planet.

I like to take words into different contexts. I am a words person in a fundamental sense. Wherever I go, that is my ultimate medium. Fernando is a visual person, and collaborating with him was easy because we have our own interests. His work is amazing and I learned a good bit from his eye for things.

4. Your work seems deeply committed to thinking about how culture is embedded in the environment and invested in the knowledge your ancestors have gleaned from the local ecologies of Louisiana. What has your project of revitalizing the Atakapa-Ishak language revealed about the links between culture and nature and has learning the ancestral language shifted your perspective in any ways?

I like to think of the things people carried in earlier times, the things Ishak People carried especially. I think of the 1735 DeBatz image mentioned above; there is an Ishak standing at the right (he is labeled using the exonym “Atakapas”). That particular Ishak is depicted in Bulbancha, a place where the Ishak without a doubt traded, but also a place a good ways from the traditional homelands of what is now Southwest Louisiana and Southeast Texas. DeBatz had an eye for physical detail, perhaps due to the fact that he worked as an engineer. Physical detail is a theme in all of his known works. The man depicted is carrying a calumet, and carrying one in Bulbancha, far from his home. Perhaps he was there for a calumet ceremony. Such a ceremony was depicted by Le Page du Pratz, as discussed by Shane Lief. Or, perhaps he was carrying a calumet seeking aid after the destruction of a village (for extensive discussion of the role of the calumet in that period of history, I refer the reader to the Ph.D. thesis of Elizabeth N. Ellis). DeBatz’s pictured Ishak has a pipe for personal use, some arrows, and an animal skin bag, but what he carried of greater value was a knowledge of languages and customs, as well as flora and fauna. Recovering that knowledge is a great and interesting task.

Making steps into Ishakkoy, “the talk of those who have been born,” has helped me to peek into the minds of the ancestors. I have been through the dictionary several times, and have taken hundreds of notecards. David Kaufman has done a terrific job of updating the orthography of the language and presenting the material originally published by Gatschet and Swanton, all of which has made the language easier to study. There is even a good bit of snark in the language I hadn’t noticed before.

Here’s a bit of reasonable speculation on my part, but the kind of stuff a person can begin to think about with some language knowledge. Breaking down some of the terms into smaller parts, one can see that some Ishakkoy terms have a bit of resistance built in. Of the two terms for “white” people, one, “šakkaw,” means a corpse. The other, “kiwilš,” might be etymologically related to the word for an egg, “kiw.” The significance of the egg is in relation to our own name for ourselves, the Ishak. The Ishakkoy word “išak” (ishak) is commonly translated as “a human being,” which isn’t wrong. However, it is possible that it is etymologically related to “iša,” a verb meaning “to be born.” As such, if the Ishak are those who have been born, the terms for colonists refer to them either as the dead or those not quite fully born.

The language reveals other concepts as well. The term used for New Year’s Day is especially noteworthy. That phrase, “kiwiliš yil hiwew hec tol,” means “happy powerful white people day.” It is an indication that colonizer time is not Ishak time. That is something I have often thought of in reference to anniversaries of colonization, such as the so-called Tricentennial of the city where I live.

Something I have thought about in writing poetry in Ishakkoy is the aesthetics of the language. I try to compose in Ishakkoy in a way that sounds good in Ishakkoy, first and foremost. The English comes later. Sometimes I wonder if the Ishakkoy poems sound good in the language to others as well. Few living people can read Ishakkoy, and some of them compose poetry and songs and stories in the language as well, especially tribal cousins Tanner Menard and Russell Reed. I really admire their work, their words, their contributions to rousing this sleepy language. Writing in this language is an act of hope, fundamentally. It is with the hope that others will use and read Ishakkoy. I am also excited about recent work by Geoffrey Kimball on the language’s grammar, which I know will lead to a greater understanding of its nuances.

5. How has climate change impacted your sense of Indigenous identity and how do you grapple with adaptation and the changing environment in your poems?

I live in a place that is disappearing. This is something often discussed on this part of the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. The very land we have walked for this long time is disappearing.

In 2021 I was surprised to find a story about the Ishak (again referred to by the exonym “Atakapa”) on the front page of Reddit, “the Front Page of the Internet.” It was taken from a volume by John Berton Gremillion and described some Ishak of old warning a colonist of an approaching hurricane, begging him and his family to find shelter in specially prepared trees where they could tie themselves up with vines and ride out the winds and waves. The colonist refused refuge and drowned with his family. I am not surprised that we could tell something was heading our way. It is a skill many Indigenous Peoples have developed. For example, the Moken, an Austronesian seafaring people, managed to survive the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami with few casualties due to observing warning signs of a dangerous wave as told in their mythology.

We are in that situation now. We are sinking in Louisiana, and Indigenous Peoples worldwide are warning of the consequences of climate change. Indigenous Nations of Louisiana such as those in and around Terrebonne Parish, in places such as the Isle de Jean Charles, are having to leave coastal areas due to rising tides and coastal erosion. In 2021 many communities of that area suffered tremendous damage from Hurricane Ida. One such place, Pointe-aux-Chenes, was emblematic, with entire neighborhoods of homes, largely occupied by Indigenous People, becoming uninhabitable. In 2020 Hurricanes Laura and Delta hammered the traditional Ishak stronghold of Tew Tul (“Tail of the Lake,” usually known by the colonizer name of “Lake Charles, Louisiana”). Many Ishak endured significant damage, including our Chief. We are facing the consequences of climate change, and we have things to say about it. I fear our warnings will not be heeded and that humanity will not make proper decisions, that we will not prepare for disaster, and that as a result, people will perish like the colonist family in Cameron Parish centuries ago.

This affects me as a person; I’ve discussed some of these issues in a blog post for Union of Concerned Scientists and talked about them in a film by the arts collective Cooking Sections. It gets into my poetry, but so far most of those poems haven’t been published yet, with a stress on “yet.”

6. How do your scientific and artistic inclinations complement and influence one another and inform your research questions and creative work? How can science, art, and activism come together most productively in the space of the Lower Mississippi and the Gulf?

I have a scientific background as a Ph.D. in cognitive science, and that influences my thinking about how people think about things. I also like to read scientific literature about flora and fauna, and that informs my work as well. There are many artists I admire locally who do scientifically informed work related to climate change and related issues, people such as Monique Verdin and Pippin Frisbie-Calder, and I could name many more.

I think Indigenous science should be studied more. We did not live in wilderness before colonization, but in areas in which the surrounding landscapes were heavily engineered, using advanced agricultural science. For those seeking an introduction to this history, I recommend Charles Mann’s popular book 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. I think about that sort of thing a good bit. Scientific research always finds a way into my writing, it seems. I’ve never tried to be an artist, but I always seem to find myself in such circles. I find that artists tackling climate change often make ample use of scientific research, and I find that wonderful.

7. Let’s end on a speculative note: What kind of future would you like to envision for Native Louisiana?

I’d like more recognition of Indigenous contributions to Louisiana foodways and musical cultures. I’d like more recognition of the fact that much of Louisiana’s Indigenous culture is preserved in the culture of Louisiana Creoles such as myself. I’d also like more discussions about tribal recognition. Louisiana is a unique place in that most of our historic Indigenous Nations are not federally recognized. This is due to deliberate acts of misclassification, often entangled with histories of enslavement of Indigenous Peoples here. Leila Blackbird’s University of New Orleans M.A. thesis contains much in the way of serious research on this topic. I also highly recommend scholarship from Brian Klopotek on the issue of recognition in Louisiana.

In 2021 Hali Dardar, Ida Aronson, and I interviewed members of federally unrecognized groups in Louisiana for a grant-funded project called Unrecognized Stories. Hali and Ida, both members of the United Houma Nation, took the project further with a media channel, Bvlbancha Public Access. It was fascinating to talk to such interesting people from various Nations. The videos of the interviews are available online and a book project is in the works. I hope to see more work like this, in which people tell their own stories of identity and discrimination and cultural preservation.

In the future I’d like Natives in Louisiana to realize the impacts of complicated histories on our lives now. I’d like Natives to not be ashamed of having African heritage. I’d like us to pass along our traditional stories and songs and plant knowledge and languages to younger generations. I’d like us to dance.

A Note on an Ishakkoy Word Change

During 2020, I was involved in several online language meetups involving Ishakkoy, which were hosted by linguists David Kaufman and Justin Southworth. These were quite useful to those of us who attended, especially with regards to learning to pronounce the language.

As part of one of these sessions in October 2020, I gave a talk entitled “Some Notes on Išakkoy Ethnic and Food Terms.” I had recently read an article in Indian Country Today, “Indigenous Languages and Race: Tribes Rethink Dated Terms,” which discusses movements to update the ethnic vocabulary in Indigenous languages, particularly with regard to African Americans. The Ishak have an interest in this because at this point all Ishak are of mixed ancestry, and most of us, myself included, are of African ancestry. If you are interested in related issues in Louisiana Indigenous communities, I recommend Brian Klopotek’s book Recognition Odysseys: Indigeneity, Race, and Federal Tribal Recognition Policy in Three Louisiana Indian Communities, as well as discussions in Andrew Jolivétte’s book Louisiana Creoles and Gabrielle Tayac’s IndiVisible.

In Ishakkoy, two terms are available for people of African descent. One is “kuš mel,” meaning literally “all black.” The other is “histoxš,” meaning a person of mixed ethnic heritage, which I reckon would include Louisiana Creoles, who have mixed Indigenous, European, and African heritage. When asked by a cousin to translate Black Lives Matter into Ishakkoy, I chose the phrase “Kuš Mel Pistaxs Uš,” which translates literally as “Life All Black Genuine/Big.” It was difficult to capture the English “matters” in Ishakkoy, but the multivalent “uš” was as close as I could get after much deliberation.

There are some issues with color terms involved in ethnic designations in Indigenous languages, as these are terms borrowed from European conceptions of ethnicity, as the Indian Country Today article linked above explains. While this is an issue with “kuš mel,” the problem brought up in our meeting was not with this term, but with another term that builds on it, one containing an offensive reference. That term is “kuš mel tukaw,” meaning “like a Black person.” It is the word in Ishakkoy for a monkey. The term is odd for a reason in addition to its offensiveness in that it is the only Ishakkoy animal term I’ve found that doesn’t refer to an animal typically found in traditional Ishak lands as either a native species (with a small “n”) or as a now-common species resulting from colonization, such as a mule.

So what did we do with this? I proposed to the group of tribal members, linguists, and others attending my online talk that we work it out. Fortunately we had a special guest in attendance that night, Donna Pierite, a member of the Tunica-Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana. Donna has been involved for many years in language revitalization efforts for the Tunica language. She is also a culture bearer across several areas, including music and storytelling, and is someone I really admire. Donna listened to this discussion carefully and her vast language knowledge came to bear. In addition to Tunica, she knows a few other languages, including Choctaw. The Choctaw term for a monkey, “hatak ahaui”–I am using Byington’s orthography here–means “raccoon man.” Donna suggested that we might consider going in that direction. For one, the term isn’t offensive. It also preserves some of the structure of the Ishakkoy term, making the word for monkey a comparison to something else. We discussed it in the group and decided to change the Ishakkoy word for monkey to “wulkišak tukaw,” meaning “like a raccoon man.”

It was empowering to change a word. The act indicates that our language is alive, not a museum piece. Even though the last fluent speakers walked on decades ago, we are still committed to using our language, and to using it without causing offense. It is an act of hope to do this, and I hope that making our language inoffensive will someday benefit future speakers. We were also honored to receive help in the process from such a noted worker in language revitalization as Donna.

Other language work that still needs to be undertaken and that interests me includes updating the species in the dictionary to more accurately reflect species from Louisiana, and adding new terms for technology and the like.

The process is ongoing, and it is a process, a long process. We are walking the road, though.